Land Development to Reduce the ‘Cone of Uncertainty’

In the tech world, stories of demand outstripping forecasts are legend. There’s Pokémon Go, whose popularity at launch so far exceeded expectations cloud servers couldn’t keep up. There’s Zoom, growing from a peak of 10 million daily meeting participants in December 2019 to 300 million in April 2020. Or ChatGPT; it’s hard to imagine anyone predicting it would reach 100 million monthly active users just two months after launch (it took TikTok nine months and Instagram two-and-a-half years to reach that level).

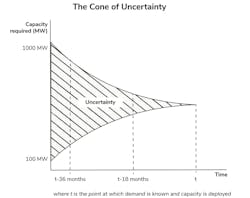

Tech companies are among the most highly sophisticated companies in the world. But the fact is, demand is really unpredictable. There are so many unknowns – about how technology will evolve, how consumers will adopt new products, and how successful the business will be at beating competitors in an extremely competitive market. High unpredictability makes it hard to accurately forecast how much data center capacity will be needed, and when, to deliver new products, allow existing products to scale, or otherwise meet demand. The longer the forecast horizon, the more uncertainty there is (i.e., it is vastly more difficult to accurately predict demand in five years than three months from now). This is what’s referred to as the cone of uncertainty with respect to demand/capacity forecasting.

The ‘cone of uncertainty’ is a common project management term; here we’re using it to demonstrate that making data center capacity decisions for an uncertain demand 3-5 years before it arrives leaves a large margin for error. For example, if a tech company forecasts 500 MW of capacity to meet consumer demand five years from now, but the company performs particularly well, actual demand may require 1000 MW of capacity. In contrast, if the company doesn’t perform well, consumer demand may require only 100 MW. That’s a big range – and represents a lot of uncertainty. If the tech company had to procure land and power today to ensure it does not “stock-out,” it would have to do so for the upper end of the forecast (1000 MW). As time passes, the tech company gets more information about consumers, competitors, and products, and the cone of uncertainty shrinks.

The long process of data center development

The first and longest part of the data center development process is what we call location strategy and site development – or more commonly referred to as site selection, acquisition, and pre-development. Tech companies have to make these decisions 3-5 years out, when the risk variance in the cone of uncertainty is largest, effectively exposing them to more risk than necessary. On the flip side, there is a significant opportunity to reduce the cone of uncertainty if tech companies don’t have to make those decisions so far before demand materializes.

Location strategy starts with identifying the target market and critical location factors. It generally takes 9-12 months or more to find a site in the right location with the right combination of “critical location factors” or CLFs. The reality is that there is no such thing as an easy site; the core markets have all been picked over. As such, having an extremely skilled development team, who know what the end user needs, is critical to ensuring predictable delivery and effective capital allocation.

The typical critical location factors for data centers involve power, fiber, land, water and wastewater (where water cooling is required), environmental and sustainability aspects, and access to skilled labor. Within each category there are a number of key capacity, cost, and schedule drivers. For example, a key land-related schedule driver is rezoning, which is often required (large sites already zoned industrial and with the necessary infrastructure are incredibly scarce) and can take 6-12 months. Sites may also require wetland mitigation or some other environmental risk mitigation, which are 1- to 2-year activities. Power is seen as one of the scarcest commodities right now but even where there is power available, utility interconnection takes time.

Shrinking the cone of uncertainty

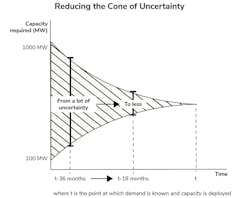

While site acquisition and pre-development are the longest-lead decisions in data center development, they are relatively inexpensive. (Even when land is expensive, it’s an asset that usually appreciates over time.) That makes it easy for a developer like Stream to justify proactive land investments in key markets. Essentially, we’re buying down lead time on our customers’ behalf – enabling them to start the process at 18-24 months instead of 3-5 years ahead of demand, thereby reducing their uncertainty and risk of purchasing land and procuring utilities.

As a data center development partner to tech companies, we take on activities such as entitlements, permitting, power acquisition, and incentives applications so that our customers can purchase capacity or sites closer to their time of need – when the cone of uncertainty is smaller. As such, they have more confidence that they are not over- or under-purchasing capacity. The result is significantly deferred and more appropriately allocated CapEx. Customers can better allocate their costs to match their demand forecasts and revenue streams and avoid stranding capital that could potentially be put to better use.

As competition for land and power intensified and capacity requirements skyrocketed, we doubled down on our commitment to our customers and launched Headwaters Site Development, an organization specifically designed to find and develop hyperscale data center sites. As an independent affiliate, Headwaters helps Stream build a land bank of sites in the right locations, with the right characteristics so our customers can make decisions about how much capacity they’re going to buy closer to when they actually need it, when they have more certainty about their demand forecast.

Taking a rigorous and methodical approach to site selection results in the highest-quality sites. The development of these sites is de-risked through a combination of sophisticated proprietary software, a 200+ item checklist, and robust diligence processes. We leverage GIS and AI where possible to expedite our desktop diligence processes, and we spend a lot of time in the field with our local utility partners and our municipality partners. We ensure that no item is left uncovered, and we address the key capacity, cost, and schedule impacts before we close on a property. If we carry a risk forward, we ensure that we have multiple strategic contingency plans in place so that development of the capacity is not impacted.

Bottom line

Most tech companies dream of growth like that of Pokémon Go, Zoom, or ChatGPT. For their capacity planners, though, it can be the stuff of nightmares. With a data center partner that has proactively invested in location strategy and development of high-quality, de-risked sites, the tech company can push back its investment from 3-5 years to about 18 months, closer to demand, and thereby shrinking the cone of uncertainty.

About the Author

Mike Lebow

Mike Lebow is Senior Vice President of Location Strategy and Development at Stream Data Centers and Co-founder and Partner at Headwaters Site Development. Mike previously worked for nearly eight years on the energy and location strategy team at Google.

Stream Data Centers builds and operates for the largest and most sophisticated hyperscalers and enterprises – 26 data centers since 1999, with over 90% of our capacity leased to the Fortune 100. Headwaters Site Development is an independent affiliate launched in 2022 in partnership with Stream to build a portfolio of available land that’s entitled and ready for customer development at the speed of the market.

Oisín Ó Murchú

Oisín Ó Murchú is Senior Vice President of Development, focused on streamlining site acquisition and development at Stream Data Centers. Oisín developed and led the global programmatic due diligence process on the same energy and location strategy team at Google.

Stream Data Centers builds and operates for the largest and most sophisticated hyperscalers and enterprises – 26 data centers since 1999, with over 90% of our capacity leased to the Fortune 100. Headwaters Site Development is an independent affiliate launched in 2022 in partnership with Stream to build a portfolio of available land that’s entitled and ready for customer development at the speed of the market.