Eight Trends That Will Shape the Data Center Industry in 2026

For much of the past decade, the data center industry has been able to speak in broad strokes. Growth was strong. Demand was durable. Power was assumed to arrive eventually. And “the data center” could still be discussed as a single, increasingly important, but largely invisible, piece of digital infrastructure.

That era is ending.

As the industry heads into 2026, the dominant forces shaping data center development are no longer additive. They are interlocking and increasingly unforgiving. AI drives density. Density drives cooling. Cooling and density drive power. Power drives site selection, timelines, capital structure, and public response. And once those forces converge, they pull the industry into places it has not always had to operate comfortably: utility planning rooms, regulatory hearings, capital committee debates, and community negotiations.

The throughline of this year’s forecast is clarity:

- Clarity about workload classes.

- Clarity about physics.

- Clarity about risk.

- And clarity about where the industry’s assumptions may no longer hold.

One of the most important shifts entering 2026 is that it may increasingly no longer be accurate, or useful, to talk about “data centers” as a single category. What public discourse often lumps together now conceals two very different realities: AI factories built around sustained, power-dense GPU utilization, and general-purpose data centers supporting a far more elastic mix of cloud, enterprise, storage, and interconnection workloads. That distinction is no longer academic. It is shaping how projects are financed, how power is delivered, how facilities are cooled, and how communities respond.

It’s also worth qualifying a line we’ve used before, and still stand by in spirit: that every data center is becoming an AI data center.

In 2026, we feel that statement is best understood more as a trajectory, and less a design brief. AI is now embedded across the data center stack: in operations, in customer workloads, in planning assumptions, and in the economics of capacity. But that does not mean every facility behaves the same way, bears the same risks, or demands the same infrastructure response. Some data centers absorb AI as one workload among many. Others are purpose-built around it, with consequences that ripple through power, cooling, capital structure, and public visibility.

The industry’s challenge and opportunity heading into 2026 is learning to operate with both truths at once: AI is everywhere, but AI does not make all data centers alike.

At the same time, the industry is becoming more self-aware. The AI buildout has not exactly slowed, but it has matured. Capital is still available, but it is no longer blind. Utilities are no longer downstream service providers; they are co-architects. Liquid cooling has moved from experiment to industrial system; but only where density demands it. Modularization and standardization are no longer about speed alone; they are about survivability. And for the first time in years, the industry is apparently beginning to plan not just for growth, but for volatility.

That does not signal retreat. It signals experience.

The eight trends that follow reflect an industry still expanding, still innovating, and still under pressure; but increasingly disciplined about where ambition meets reality. They trace how AI reshapes infrastructure without consuming it entirely; how power becomes the central organizing constraint; how execution overtakes novelty as the competitive advantage; and how a sector long accustomed to momentum begins designing for durability.

If there is a single lesson embedded in this year’s forecast, it is this: the frontier has moved inward. The challenges shaping 2026 are less about discovering what’s next than about managing what scale actually demands.

What follows is our view of the eight trends that will define that reckoning.

1. AI Energy Demand Defines a Split Between AI Factories and General-Purpose Data Centers and Pulls the Industry Into the Public Arena

In 2026, it may no longer be accurate or useful to talk about “data centers” as a single category.

What are often grouped together in public debate are, in practice, two very different classes of infrastructure:

- AI factories, designed around sustained GPU utilization, extreme rack densities, and tightly coupled power-and-cooling systems.

- General-purpose data centers, supporting cloud, enterprise, storage, interconnection, and mixed workloads with far more elastic demand profiles.

This distinction matters because the most acute energy stress and, arguably, the bulk of public scrutiny has concentrated around AI factories, not the broader data center ecosystem.

AI factories behave differently. Their loads are larger, less interruptible, and more visible. Campuses routinely plan for hundreds of megawatts of firm power, with timelines that compress utility planning cycles and push infrastructure decisions upstream. Their tolerance for curtailment is low. Their demand profiles look less like traditional commercial load and more like industrial infrastructure.

General-purpose data centers remain constrained, but more adaptable. They can phase capacity, diversify workloads, and absorb efficiency gains more gradually. In many cases, they are now being pulled into debates sparked by AI factories that operate at an entirely different scale.

This divergence has a direct social consequence.

As AI factories grow larger and more concentrated, they increasingly lose the industry’s long-standing advantage of invisibility. Utilities, regulators, local governments, and communities are no longer reacting to “data centers” in the abstract; they are responding to very specific projects with very specific impacts on grid capacity, land use, water, and long-term energy planning.

By 2026, data centers, particularly AI factories, are being treated less as optional economic development projects and more as critical infrastructure, alongside transportation, energy, and water systems. That reframing brings stature, but also scrutiny in the form of:

- More formal load-prioritization debates.

- Greater regulatory visibility at the state and regional level.

- Expectations around resilience, transparency, and continuity planning.

- Public questions about who benefits, who pays, and who bears risk.

Importantly, this scrutiny is not evenly distributed. It follows density and power. The sharper the load profile, the brighter the spotlight.

The result is a more precise, but more demanding, conversation. In 2026, the question is no longer just whether “data centers” are straining the grid. It is which class of data center, under what assumptions, and at what scale.

Under this framing, the industry gains clarity, but loses the comfort of being misunderstood.

Onsite Power Moves From Contingency to Architecture

One of the clearest signals embedded in the AI factory versus general-purpose data center split is how power is being sourced.

For decades, behind-the-meter generation was treated more as a contingency: backup power, resilience insurance, and/or a niche solution for remote sites. By 2026, that framing no longer holds for AI factory campuses. In these environments, onsite power is increasingly part of the primary architecture.

The reason is straightforward. AI factories combine three characteristics that strain traditional grid-only models:

- Scale - Single-tenant or tightly clustered loads routinely planning for hundreds of megawatts.

- Continuity - Sustained, non-interruptible utilization profiles with low tolerance for curtailment.

- Speed - Development timelines that move faster than transmission upgrades and interconnection queues.

Utilities are not failing. They are simply being asked to do something grids were not designed to do quickly: absorb massive, fast-ramping industrial-scale loads on compressed timelines.

The industry’s response has been pragmatic rather than ideological. Natural gas has emerged as the near-term bridge not because it is fashionable, but because it is dispatchable, scalable, and deployable within realistic time horizons. For many AI factory projects, gas-fired generation, sometimes paired with carbon capture planning or hydrogen-blending roadmaps, is the only way to reconcile density with delivery schedules.

At the same time, long-cycle power strategies are being layered in. Nuclear, particularly small modular reactors (SMR) and microreactors, has now obviously moved from theoretical alignment to strategic positioning. While few operators expect meaningful nuclear capacity to materialize this decade, the planning assumptions are already influencing site selection, land control, and partnership structures.

What is striking is how asymmetric this shift remains.

General-purpose data centers continue to rely primarily on the grid, augmented by efficiency gains, phased delivery, and demand flexibility. AI factories, by contrast, are forcing the issue. Their power requirements are so concentrated, and frankly so visible, that they are accelerating new models of generation ownership, co-investment, and hybrid supply.

The result is not grid abandonment by any means, but grid re-negotiation. Onsite power does not replace utilities; it reshapes the relationship. Developers are increasingly by necessity co-planning load, generation, and phasing from day one, rather than treating power as a downstream procurement exercise.

In 2026, behind-the-meter power is no longer a signal of exceptionalism. It's a marker of workload class. Where density demands it, onsite generation moves from the margins to the blueprint.

2. The AI Infrastructure “Bubble” Debate Moves Inside the Industry as Power Becomes a Negotiated Relationship

By 2026, concerns about whether parts of the AI infrastructure buildout are running ahead of sustainable demand are no longer whispered. They are increasingly debated in plain view inside boardrooms, earnings calls, utility planning sessions, and capital committees.

This is not a blanket bubble call. Demand for AI compute remains real and growing. But the shape of the buildout, particularly GPU-dense capacity optimized for large-scale training workloads, has introduced new questions about utilization durability, asset lifecycles, and financial exposure. Rapid hardware iteration, short depreciation curves, and the narrowing reuse profile of AI-factory infrastructure have made “build it and they will come” a harder assumption to defend.

What has sharpened that debate is power.

In earlier eras, power was something data center developers procured after selecting a site. In 2026, power is increasingly something that must be co-designed from the outset, and utilities are asserting themselves accordingly. Large AI-oriented projects are being asked to phase load, accept curtailment provisions, co-invest in generation or transmission upgrades, and, in some cases, relocate altogether to align with grid realities.

That shift has important implications for the bubble conversation. Projects that once penciled out on paper can stall when power delivery timelines stretch, interconnection conditions tighten, or utilities impose behavioral constraints on load. In that environment, speculative capacity becomes riskier not because AI demand disappears, but because power delivery, not capital availability, becomes the gating variable.

Developers and investors are responding with greater discipline. Phased campuses, modular delivery, optional expansion rights, and diversified workload strategies are increasingly favored over monolithic, all-at-once builds. Capital remains available, but it is more selective: rewarding projects that demonstrate power certainty, flexibility, and credible paths to sustained utilization.

The result in 2026 is not an industry in retreat, but one in recalibration. The AI infrastructure boom continues, but it does so under tighter scrutiny from utilities, regulators, and investors alike. Power is no longer a background assumption. It is an active participant in shaping which projects move forward, at what scale, and on what terms.

In that sense, the bubble debate is less about whether AI demand is real, and more about who bears the risk when infrastructure ambitions collide with grid constraints.

3. AI Integration Deepens Even as GPU-Centric Economics Remain Unsettled and Capital Discipline Sharpens

As the industry heads into 2026, artificial intelligence is no longer an overlay on big-picture data center strategy. It is embedded across the stack; from facility design assumptions and cooling architectures to operational tooling, workload scheduling, and infrastructure planning.

At the same time, the economics of accelerated compute remain unsettled.

The industry spent much of 2024 and 2025 building GPU-centric capacity at unprecedented speed, driven by hyperscale demand, competitive pressure, and the fear of missing the AI moment. What emerged alongside that buildout was a more sober understanding of the tradeoffs involved. Rapid hardware iteration, high capital intensity, and uncertain utilization curves have introduced meaningful balance-sheet and lifecycle risk; particularly for assets optimized narrowly around specific generations of GPUs or training workloads.

As a result, 2026 opens with an industry that is far more fluent in AI infrastructure, but less naïve about its financial implications. This is where capital discipline begins to matter more than capital abundance.

Money remains available for data center and AI infrastructure projects, but it is no longer indiscriminate. Investors, lenders, and partners are increasingly separating AI factories from general-purpose data centers, short-cycle compute risk from long-cycle real estate risk, and speculative capacity from projects anchored by durable contracts or diversified workloads. Coverage from The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, and Bloomberg over the past year has consistently highlighted this shift, noting greater scrutiny of utilization assumptions, depreciation schedules, and exit flexibility tied to GPU-heavy builds.

The consequence is a quieter but significant change in who wins deals. Speed alone is no longer the decisive advantage. The developers and operators that attract capital in 2026 are those that can clearly articulate risk: how assets can be reused, how density can be dialed up or down, how power and cooling investments remain valuable across multiple compute generations, and how exposure is phased rather than front-loaded.

AI integration continues to deepen across the industry but it does so within a more disciplined capital framework. Facilities are still being built. AI capacity is still expanding. What changes is the tone of the conversation: from growth-at-any-cost to growth-with-options.

In that sense, the maturation of AI infrastructure in 2026 is not marked by slower adoption, but by better questions being asked earlier; by boards, investors, and operators who now understand that AI fluency does not eliminate risk, it simply makes it easier to see.

4. The MegaCampus Becomes an AI Factory and Utilities Become Co-Architects

In 2026, the megacampus is no longer a generic hyperscale construct. It is increasingly an AI factory campus, and that shift has permanently altered the relationship between data center developers and utilities.

This transition is being driven most forcefully by the major hyperscalers (AWS, Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Oracle) whose AI factory requirements compress timelines and concentrate demand at a scale utilities cannot treat as incremental. These companies are no longer adding load at the margins. They are reshaping regional power planning assumptions.

In earlier eras, utilities were service providers. Power was requested, modeled, queued, and delivered, eventually. That model breaks down when campuses plan for hundreds of megawatts of sustained, non-interruptible load on timelines that outpace transmission upgrades and generation build-outs.

As a result, utilities are no longer downstream participants in AI factory development. They are effectively becoming co-architects, engaged before site plans are finalized and often before land is fully controlled. Power strategy now gates everything that follows: campus layout, phasing, cooling architecture, capital structure, and even customer mix.

This co-architect role shows up in several concrete ways:

- Phased load agreements that tie capacity delivery to infrastructure milestones.

- Co-investment models in substations, generation, or transmission.

- Load shaping and curtailment frameworks negotiated up front, not imposed later.

- Locational discipline, with utilities increasingly steering projects toward grid-advantaged zones rather than reacting to developer preference.

In this environment, the megacampus era does not simply expand. It specializes.

Mapping the Power Stack: Gas, Nuclear, and Hybrid Models

What has also become clearer by 2026 is how different power sources align to different time horizons, and how utilities and hyperscalers are orchestrating those layers together.

Natural gas occupies the near-term execution layer. It is dispatchable, scalable, and deployable within timelines that match AI factory demand. For hyperscalers seeking speed-to-market, gas-fired generation (whether utility-owned, developer-owned, or structured through long-term supply agreements) has become the default bridge where grid capacity lags load growth. This is not a philosophical choice. It is a scheduling one.

Nuclear, particularly small modular reactors and microreactors, occupies the long-cycle planning layer. Hyperscalers and utilities alike are increasingly aligning land control, permitting strategy, and partnership structures around future nuclear potential, even as most acknowledge that meaningful capacity will arrive later in the decade. Nuclear is shaping where megacampuses are planned, even if it does not yet power them.

Hybrid models now define the middle ground. These combine grid supply, onsite generation, phased delivery, storage, and future-proofing assumptions into a single integrated plan. In practice, this is where utility co-architecture is most visible. Hyperscalers, in particular, are increasingly willing to engage utilities directly on generation strategy; co-planning gas capacity in the near term, reserving nuclear-adjacent land for the long term, and structuring hybrid delivery models that smaller operators cannot replicate.

What emerges is a more explicit division of labor. Utilities retain their central role in grid reliability and long-term planning. Developers translate hyperscale requirements into buildable form. Hyperscalers accept that power can no longer be abstracted away from design.

The megacampus era did not arrive in 2026. It consolidated - and learned to speak fluently with the grid.

5. Pricing Pressure Pushes Demand Outward but Power Remains the Constraint, Forcing a Turn Toward Standardization

By 2026, rising pricing and limited deliverable supply in core data center markets continue to push demand outward. Larger continuous requirements (particularly blocks of 10 megawatts and above) face the sharpest pressure, driven by hyperscale absorption, constrained power availability, and persistently elevated construction costs.

But this was never simply a geography story.

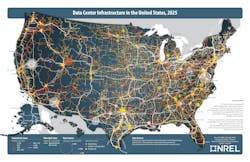

Even as developers and hyperscale partners widen their search radius into secondary and tertiary markets, the same constraint follows them: power. In many emerging regions, land is available, entitlements are workable, and local officials are receptive...but utility headroom remains limited. Interconnection timelines, substation capacity, and grid upgrade requirements may increasingly prove more decisive than zoning, tax incentives, or political goodwill.

Industry analysis from CBRE, JLL, Cushman & Wakefield, and Reuters over the past year has consistently shown that new markets do not eliminate constraints so much as reintroduce them under different utility footprints. The outward push continues, but it is bounded by the same physical realities.

As a result, the industry’s response in 2026 is probably not just geographic expansion, but also operational compression; and that is where standardization reasserts itself.

After years of bespoke design driven by hyperscale customization and early AI experimentation, data center development is swinging back toward standardization: not for elegance or theoretical efficiency, but for survivability. Repeatable power blocks, modular cooling architectures, factory-built subsystems, and standardized electrical rooms increasingly replace one-off designs that slow delivery, complicate commissioning, and collide with utility timelines.

This shift is particularly visible in projects tied to large, continuous loads. Hyperscalers still drive requirements; but even they are showing greater tolerance for standardized delivery models when speed, phasing, and power coordination matter more than architectural novelty. Vendor lock-in, once resisted, is becoming more quietly accepted as the price of execution certainty.

Standardization also serves a financial purpose. When pricing pressure is high and power delivery uncertain, developers need to reduce the variables they can control. Standardized designs shorten timelines, lower construction risk, and make it easier to phase capacity in alignment with utility delivery schedules. They also allow operators to make clearer, more defensible commitments to customers at a time when overpromising has become increasingly risky.

In that sense, standardization becomes the industry’s coping mechanism for constraint. It is how operators keep promises in markets where supply is tight, pricing is unforgiving, and power cannot be taken for granted. The outward push continues in 2026, but it does so with fewer design experiments, tighter playbooks, and a growing recognition that repeatability is now a competitive advantage.

6. Liquid Cooling Will Become Table Stakes, But Mainly Where Density Demands It

By 2026, liquid cooling is obviously now very far from a speculative technology. But neither is it a universal mandate.

What the industry has learned, often through hard experience, is that deploying liquid cooling at scale is less about thermodynamics than execution. The real inflection point is not whether liquid cooling works. It does. The question is where it can be deployed repeatably, operated safely, and maintained without friction as fleets scale from pilots to production.

The Physical Reality: Designing for Scale, Not Demos

On a physical track, direct-to-chip liquid cooling becomes standard in AI factory environments where sustained GPU utilization and extreme rack densities overwhelm the limits of air. These facilities are designed from inception around liquid loops, higher inlet temperatures, and thermal architectures optimized for continuous, high-intensity workloads. Cooling is no longer an accessory system layered onto the building. It is a defining design constraint that shapes floor loading, piping routes, redundancy models, and commissioning timelines.

As AI factories scale, operators increasingly standardize around repeatable cooling blocks rather than bespoke hall-by-hall designs. Manifold layouts, CDU placement, leak-detection systems, and maintenance access are engineered for replication, not experimentation. The priority shifts from achieving maximum theoretical efficiency to ensuring predictable performance across hundreds or thousands of racks.

General-purpose data centers follow a different path. Rather than liquid-first designs, most continue adopting hybrid approaches: rear-door heat exchangers, localized liquid-cooled zones, and selective support for high-density clusters. This allows operators to support AI workloads without committing entire facilities to liquid infrastructure that may limit future reuse. In these environments, liquid cooling is an overlay, not the foundation.

Immersion: Operationally Viable, Strategically Selective

Immersion cooling continues to advance, validate, and professionalize - but selectively. By 2026, it has proven itself operationally viable in specific AI factory use cases where density, space efficiency, or thermal headroom justify the added complexity. However, immersion remains uneven in its operational footprint.

The barriers are not technical so much as logistical and organizational: fluid handling, component compatibility, maintenance workflows, vendor coordination, and regulatory familiarity. Immersion systems demand new service models, retraining of technicians, and tighter integration between IT and facilities teams. For many operators, those tradeoffs remain acceptable only in tightly controlled, purpose-built environments.

As a result, in 2026 immersion probably does not flip into a mainstream default across hyperscale or colocation design. It matures, but remains intentional, not ubiquitous.

The Structural Shift: Cooling Becomes an O&M Discipline

On a structural track, cooling strategy becomes explicitly workload-specific rather than aspirational. The industry moves away from one-size-fits-all narratives toward pragmatic segmentation:

- AI factories optimize for sustained thermal performance and continuous utilization.

- General-purpose facilities optimize for adaptability, serviceability, and long-term reuse.

- Hybrid designs bridge the two where economics and customer mix demand it.

As fleets scale, operations and maintenance move to the center of cooling decisions. Leak management, spare-parts logistics, service intervals, technician training, and failure isolation increasingly outweigh marginal gains in efficiency. Designs that are repeatable, serviceable, and compatible with evolving hardware roadmaps gain favor over more exotic configurations that introduce operational risk.

This operational reality reinforces the turn toward standardization seen elsewhere in the industry. Liquid cooling systems are increasingly specified, installed, and maintained as industrial infrastructure: less bespoke, more modular, and tightly integrated with power and monitoring systems.

The 2026 Reality Check

The net effect in 2026 is clarity. Liquid cooling becomes essential where density demands it but optional where it does not. The industry stops arguing whether liquid cooling is “the future” and starts deciding precisely where, how, and for which workloads it belongs.

The winners are not the operators with the most aggressive cooling concepts, but those who can deploy liquid cooling at scale: reliably, repeatably, and without disrupting the rest of the facility. In that sense, liquid cooling’s maturation mirrors the broader trajectory of the industry itself: fewer experiments, tighter playbooks, and a growing emphasis on execution over ambition.

7. Speed Meets Gravity: Accelerated Deployment Tests the Limits of Edge Scale-Out

As the data center industry moves into 2026, the impulse to build faster is unmistakable. Modular construction, prefabrication, standardized power blocks, and repeatable designs are in no way experimental techniques; they are becoming default responses to compressed timelines, constrained power availability, and hyperscale demand.

What remains in flux is where that acceleration ultimately expresses itself.

For years, edge computing has been positioned as a counterweight to hyperscale concentration. The logic is straightforward: latency-sensitive workloads, distributed inference, and data-local processing should push compute outward, closer to users, devices, and data sources. In 2026, those use cases continue to grow, but they coexist with a persistent gravitational pull toward centralized infrastructure.

Power and Physics Still Favor the Core

The most demanding AI workloads (training, large-scale inference, and sustained GPU utilization) continue to favor centralized environments. AI factories require firm power, dense interconnection, liquid cooling at scale, and operational maturity that remains difficult to replicate economically at the edge.

As a result, even as edge deployments expand, the largest capital commitments remain anchored to megacampuses that can support utility coordination, onsite or hybrid power strategies, and standardized delivery at scale. The industry’s fastest-growing workloads still pull infrastructure inward, not outward.

Where Edge Expansion Is Likely to Materialize

That does not mean edge infrastructure stalls. Instead, it becomes more targeted.

In 2026, edge-leaning deployments are most likely to gain traction in vertical-specific use cases rather than as a generalized alternative to centralized AI infrastructure. These include healthcare imaging and diagnostics, manufacturing and logistics automation, autonomous and transportation systems, and retail or municipal analytics where latency, data locality, or regulatory constraints justify localized compute.

Geographically, this expansion favors secondary markets that combine strong fiber connectivity, moderate power availability, and proximity to population centers; markets such as Raleigh-Durham, Minneapolis, Salt Lake City, Denver, and Columbus fit this bill. These locations sit close enough to users to matter, but are large enough to support repeatable deployment models.

Modular and Prefabricated By Design

Modular and prefabricated data center designs play a central role in this evolution. In edge contexts, these approaches are not about maximizing density; they are about bounding complexity. Factory-built power and cooling systems, containerized enclosures, and pre-engineered modules shorten deployment timelines and reduce execution risk.

These designs emphasize scale-out rather than scale-up. They trade peak density for predictability, accepting smaller footprints and lower per-site capacity in exchange for faster delivery and clearer operational limits. In doing so, they make edge deployments viable where bespoke builds would struggle to pencil.

A More Disciplined Topology Emerges

By 2026, the industry is converging on a more nuanced infrastructure topology. Dense, power-intensive AI factories anchor the core. Lighter, purpose-built facilities extend compute outward where workloads demand proximity rather than sheer scale.

Accelerated deployment strategies are central to both; but they express themselves differently depending on physics, power, and workload profile. Speed matters. So do boundaries.

Bottom line: The edge scale-out continues in 2026, but within limits defined by gravity.

8. The Data Center Industry Begins Planning for Volatility, Not Just Growth

This may be the most under-discussed shift heading into 2026.

After several years of relentless expansion driven first by cloud, then by AI, the data center industry now begins to quietly ask different questions. Not about how fast it can build, but about how its assets behave if conditions change.

In 2026, forward-looking operators, developers, and investors may increasingly ask:

- What happens if AI demand moderates or fragments?

- How reusable are these facilities beyond their first workload?

- How do you pause, phase, or mothball capacity without writing it off?

- What does a soft landing look like in an industry built for acceleration?

This line of inquiry is not pessimism. It indicates institutional maturity.

Designing for Optionality, Not Just Peak Demand

On the physical track, facilities are increasingly designed with reuse, reconfiguration, and staged expansion in mind. The industry moves away from single-purpose, all-or-nothing builds toward layouts that can absorb change.

That shows up in more flexible power distribution, modular cooling zones, convertible halls, and campus designs that allow capacity to be added (or deferred) without stranding sunk costs. Even AI factory projects may begin incorporating assumptions about secondary uses, phased densification, or partial repurposing over time.

The goal is not to dilute performance at peak demand. It is to preserve value if demand curves flatten, shift, or bifurcate.

Capital Structures Begin to Reflect Cycles

On the structural track, capital discipline deepens. In 2026, the industry begins planning explicitly for variability rather than assuming uninterrupted growth.

Developers and investors pay closer attention to duration mismatch, utilization risk, and depreciation cycles, particularly in GPU-dense environments where hardware refresh timelines move faster than real estate amortization. Lease structures, joint ventures, and financing models increasingly reflect phased delivery, optional expansion, and downside protection.

This trend does not signal retreat from AI infrastructure. It signals a more realistic understanding of how technology cycles behave over time.

From Expansion Mindset to Resilience Mindset

What changes most in 2026 is tone.

The industry does not stop building. It does not pull back from AI. But it begins to acknowledge that infrastructure built at this scale must endure more than one market condition. Designing for volatility - operational, financial, and technological - becomes part of responsible planning rather than an admission of doubt.

In that sense, this forecast point is less about preparing for decline than about earning durability. The data center industry enters 2026 still expanding, but no longer pretending that growth is the only state it needs to survive.

Honorable Mentions: 7 Additional Pressure Points the Data Center Industry Can’t Ignore in 2026

Beyond these eight defining trends, a set of quieter shifts is reshaping how the industry plans, staffs, and operates at scale. These themes may not define the center of gravity in 2026, but they increasingly influence how the industry executes against its core challenges.

In many cases, they function less as standalone trends than as pressure points: areas where technology, operations, and institutional behavior are quietly evolving in response to scale.

1. Digital Twins Move From Planning Tool to Operational Infrastructure

Digital twins are shedding their early identity as design-time visualization aids and moving toward something more consequential: an operational abstraction layer for complex infrastructure. In 2026, their value increasingly lies in real-time modeling of power flows, thermal behavior, equipment stress, and failure propagation; particularly in AI-dense environments where margins for error are thin.

What is changing is not the concept, but the use case. As facilities grow larger and more interdependent, operators need ways to simulate decisions before executing them: i.e. how a cooling adjustment affects power draw, how phased expansion alters redundancy, how maintenance schedules intersect with utilization peaks. Digital twins offer a way to make those tradeoffs explicit.

Adoption remains uneven. Integration with legacy systems is complex, data fidelity varies, and organizational ownership is often unclear. But where scale and density converge, digital twins are becoming increasingly less optional, and more infrastructural.

2. Workforce Pressures Shift From Hiring to Retention and Specialization

The workforce challenge facing the data center industry does not lessen in 2026. It matures.

The most acute constraint is no longer raw headcount, but the availability of highly specific skill combinations: technicians fluent in liquid cooling systems, engineers comfortable operating at higher voltages, managers capable of bridging IT, facilities, and energy disciplines. As systems become more integrated, the cost of turnover rises.

This shifts the focus from hiring to retention, training, and institutional continuity. Knowledge transfer, career pathways, and operational resilience increasingly matter as much as staffing numbers. In an environment where execution risk is high, experience becomes an asset that compounds over time.

3. Energy Storage Becomes a Conditional Infrastructure Lever

By 2026, battery and energy storage systems are no longer theoretical in the data center industry, but neither are they universal. Storage is increasingly evaluated as a situational tool for load shaping, interconnection timing, and resilience, particularly in regions with constrained grids or volatile delivery schedules.

What limits broader adoption is not relevance, but variability. The value of storage differs dramatically by geography, regulatory framework, utility posture, and workload profile. In some markets, it materially alters execution risk or accelerates delivery. In others, it adds cost without unlocking meaningful capacity.

The result is not neglect, but selectivity. Energy storage is becoming an important part of the power toolkit; deployed deliberately where it changes outcomes, rather than assumed as a default layer of every data center design.

4. Cybersecurity Expands From IT Concern to Infrastructure Reality

As data centers become more software-defined, energy-integrated, and operationally interconnected, cybersecurity expands beyond the traditional IT perimeter. In 2026, attention increasingly turns to operational technology (OT), energy interfaces, building management systems, and the control layers that tie physical infrastructure together.

This shift is still early. Many organizations remain structured around legacy distinctions between IT and facilities. But the direction is clear: as infrastructure becomes programmable, it also becomes addressable, and therefore vulnerable.

Cybersecurity is beginning to be discussed not just as a compliance requirement, but as an element of infrastructure resilience. That conversation is only starting, but it will grow louder as systems converge.

5. Sustainability Becomes a Tradeoff Exercise, Not a Slogan

By 2026, sustainability discussions in the data center industry are more pragmatic and more constrained.

Ambitious targets remain, but the industry increasingly acknowledges the tradeoffs involved in meeting them under real-world conditions. Speed-to-market, grid reliability, power availability, and regional constraints all shape what is achievable. The result is a shift from aspirational framing toward explicit prioritization.

This does not represent abandonment of sustainability goals. It reflects a more honest reckoning with scale. Sustainability becomes something that must be negotiated between power sources, timelines, and stakeholders - rather than assumed as a default outcome.

6. Nuclear Power Shapes Planning Long Before It Shapes Power Bills

Nuclear energy continues to exert outsized influence on data center planning despite limited near-term deployment. Small modular reactors and microreactors increasingly inform site selection, land control strategies, and long-term utility relationships, even as most operators acknowledge that meaningful capacity remains years away.

In 2026, nuclear functions less as an execution tool than as a strategic signal. It shapes where campuses are planned, how partnerships are structured, and which regions are considered viable for long-duration growth. Its impact is real, but temporal.

7. Onsite and Hybrid Power Models Multiply Without Converging

Beyond the headline narratives of gas and nuclear, the industry experiments with an expanding array of hybrid power models: partial generation ownership, utility co-investment, phased interconnection, storage overlays, and future-fuel optionality.

What defines 2026 is not convergence, but diversity. Power strategies are increasingly bespoke, shaped by geography, utility posture, regulatory frameworks, and workload class. This fragmentation reflects adaptation, not confusion. It is the natural outcome of an industry operating under constraint.

Over time, patterns may emerge. In the near term, the power stack remains situational.

Why These Forces Matter

Individually, none of these "pressure point" themes defines the data center industry in 2026. Collectively, they explain how the industry is learning to operate at scale: absorbing complexity, accepting tradeoffs, and prioritizing execution over novelty.

They are the connective tissue beneath the headline trends. And they suggest that the most important changes underway are not always the loudest ones, but the ones quietly reshaping how decisions get made.

Why These Trends—and Why Now

Taken together, these trends are less a forecast of disruption than a portrait of an industry growing into its own consequences.

What distinguishes 2026 from earlier cycles is not the emergence of any single technology or business model, but the convergence of scale, visibility, and constraint. AI did not merely increase demand; it exposed the limits of existing assumptions about power, cooling, capital, and execution. Growth did not slow: but it became heavier, more physical, and harder to abstract away.

That is why so many of this year’s defining forces are not about invention, but about translation: translating AI ambition into buildable infrastructure, translating utility realities into development strategy, translating capital availability into disciplined deployment, and translating public scrutiny into operational legitimacy.

In earlier eras, the data center industry could afford to treat friction as temporary. Power would arrive. Permits would clear. Communities would acclimate. Capital would follow growth. In 2026, those assumptions no longer hold uniformly, and the industry knows it.

What replaces them is not retrenchment, but realism.

The most telling shift running through this forecast is the industry’s growing comfort with specificity. Not every data center is the same. Not every workload justifies the same density. Not every market can absorb the same scale. And not every year will reward speed over durability. These distinctions, once glossed over, are now central to how projects are conceived, financed, and delivered.

That is why the “frontier” in this forecast looks different than it once did. It is less about what comes next and more about how well the industry operates at the scale it has already reached. Execution, coordination, and resilience have become as strategic as technology choice.

If there is a throughline to 2026, it is this: the data center industry is no longer building toward inevitability. It is building toward sustainability in the broadest sense: technical, financial, operational, and social.

These trends matter now because the industry has reached a point where momentum alone is no longer sufficient. The next phase will be defined not by who builds the most, but by who builds with the clearest understanding of risk, responsibility, and reuse.

That doesn't mean the end of growth. It may denote the beginning of a new kind of durability.

At Data Center Frontier, we talk the industry talk and walk the industry walk. In that spirit, DCF Staff members may occasionally use AI tools to assist with content. Elements of this article were created with help from OpenAI's GPT5.

Keep pace with the fast-moving world of data centers and cloud computing by connecting with Data Center Frontier on LinkedIn, following us on X/Twitter and Facebook, as well as on BlueSky, and signing up for our weekly newsletters using the form below.

About the Author

Matt Vincent

A B2B technology journalist and editor with more than two decades of experience, Matt Vincent is Editor in Chief of Data Center Frontier.